2025-12-26

Lifecycles of Gods

How human societies create and evolve their deities

Tags: Material Analysis, Psychology, History, Religion

Human history is not a straight line toward morality or enlightenment. It is the chronology of human imagination confronted with survival. Gods emerge where humans feel powerless, evolve where humans gain mastery, and fade where humans no longer need them. They are not moral authorities. They are tools given life by necessity. Their power is not intrinsic; it is a reflection of how useful they are to human society. Those that survive do so by serving a purpose; those that vanish are forgotten because they no longer solve a problem humans face.

Nature as the First Pantheon

Gods born of utility and fear

"Thor's Fight with the Giants" (Tors strid med jättarna) by Mårten Eskil Winge (1872)

Early humans faced a world indifferent to their intentions. Storms, disease, fire, predators: survival was fragile and knowledge limited. Gods emerged as interfaces with what humans could not control, and their power depended entirely on the attention, ritual, and fear humans invested.

- Greek: Zeus – lightning must be feared and appeased to protect crops

- Norse: Thor – storm and chaos require ritual attention

- Vedic (Indian): Varuna – cosmic order ensures human survival

- Vedic (Indian): Agni – sacrificial fire bridges humans and the unpredictable

- Mesopotamian: Enlil – storms can destroy or bless

- Egyptian: Set – desert and disorder must be respected

These gods are potent because humans need them to explain and influence nature. When survival became manageable, fire controlled, crops protected, predators avoided, their immediate utility declined. Some survive in adapted forms: Thor, Zeus, and Set persist in myth as symbols of strength, authority, or chaos, but their original power over life and death is gone.

Humans found comfort in the idea that these gods could be negotiated with, appeased, or invoked. Their rituals structured human interaction with a dangerous world. But as humans mastered nature, the direct need for these deities diminished. All that was unexplainable became explainable. "If there is no rain, did you not sacrifice a goat?" became a sound explanation when there was no better answer to give.

The weak human society needed strong gods. They needed a reason to live life in a dangerous world. The gods were simple tools to manage that fear. They had human emotions, human flaws, and human desires. They were not perfect. They were not omnipotent. They were just powerful enough to keep nature in line.

Society as the New Arena

Gods of order and ethical utility

"Christ driving the money-changers from the Temple" by Cecco del Caravaggio (1601)

As humans stabilised food and built societies, the threat of nature receded. The most pressing conflicts were now human-made: law, hierarchy, empire, inequality. Gods adapted to remain relevant, gaining power through their usefulness as guides and critics of social life.

Gods as Social Guides

- Buddha: critiques caste and ritual, offering liberation from social constraint

- Jesus: challenges empire, offering moral framework for communities

- Shiva: destroys stagnation, enabling societal renewal

- Muruga: inspires youthful resistance against oppression

- Ma’at (Egypt): enforces justice and social balance

- Athena (Greek): embodies wisdom for civic and military strategy

Their potency is measured by their ability to shape human behaviour and sustain social cohesion. Gods that failed to serve society’s needs, local or minor deities, were gradually forgotten. Those whose teachings remained applicable endured, because humans still derived practical or ethical guidance from them.

Gods as Tools of Power

Gods became tools of power for rulers and elites. By aligning themselves with divine authority, kings, emperors, and priests legitimised their rule. The utility of gods extended beyond personal salvation to political control. This dual role reinforced their importance in human society. Gods became a tool of both personal and political utility.

The same gods that offered resistance also legitimised power structures. Their survival depended on their ability to navigate this complex relationship with human society. Humans needed gods to maintain order, but they also needed gods to challenge that order when it became oppressive.

Abstract and Internalised Gods

From pantheon to principle

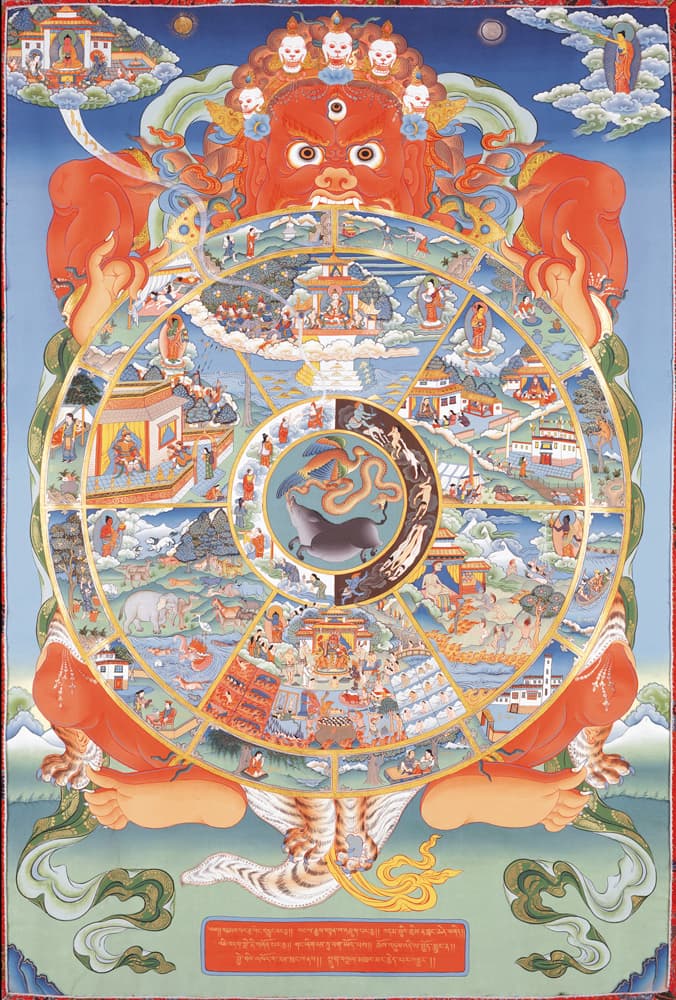

"The Wheel of Life" (Bhavachakra)

As societies scale, oppression becomes procedural, distant, and abstract. Gods themselves become concepts, virtues, and principles, surviving only because they serve human systems rather than demand direct worship.

- Roman Fides, Justitia – maintain trust and justice in civic life

- Chinese Confucian and Taoist principles – stabilise governance and social norms

- Hindu Dharma – codifies ethical action in everyday life

These are gods without faces, potent because humans rely on them to organise society and personal conduct. Deities tied to obsolete fears or localised threats vanish. Only those that continue to solve a problem, moral, legal, or social, retain influence.

The modern world is full of such abstractions. Justice, freedom, equality: these are not gods in the traditional sense, but they function as secular deities, commanding devotion, shaping behaviour, and structuring societies. Their power is not mystical; it is practical. They endure because humans continue to find them useful in navigating complex social landscapes. The texts became laws, the rituals became customs, and the gods became ideals. Their survival is a testament to their continued relevance in human life. Rights that were needed in the nation-state were "endowed by their Creator" and thus became secular gods in their own right.

Modern Gods

Internalised, insatiable, invisible

Gods Within

Today, divinity often resides inside the human mind. Success, productivity, happiness, authenticity: these are gods whose power comes entirely from human dependence. Their temples are offices, their rituals optimisation, their sacrifices sleep.

- Unlike Thor, they cannot strike physically; they dominate through expectation and desire

- Unlike Buddha, they rarely forgive; they demand constant effort and vigilance

They endure because humans continue to obey them, consciously or unconsciously. When they cease to serve, when values shift, culture changes, or desires evolve, they lose influence, fade, and die. Their strength is not intrinsic. It is purely the reflection of human utility.

Personal Pantheons

A more personal sense of godhood has emerged. The self is now a temple, and self-improvement a ritual. The gods of old have not disappeared; they have been internalised. They demand constant attention, shaping behaviour through psychological and social mechanisms rather than overt worship.

Their power is insatiable because human desires are endless. They thrive on the perpetual pursuit of betterment, success, and fulfilment. This leads to a paradox: the more humans chase these gods, the more elusive they become. Satisfaction is fleeting, and the cycle of desire continues unabated. The gods of modernity are not static; they evolve with human aspirations.

Each person defines their sense of divinity, creating a personal pantheon that reflects individual values and goals. Their survival depends on their ability to adapt to changing human needs and desires. This fills the void left by the alienation of workers in an industrial society. The gods are now within, demanding constant attention and shaping behaviour through internalised expectations.

Internal Navigation

Some might argue that it is the same as before, but the mechanism is different. At the point of humans resigning to the complexity of the world, the gods become not a tool of organisation but a tool of personal navigation. The gods are no longer external forces to be appeased but internal guides to be followed. Their power is not in their ability to control the world but in their ability to shape the individual’s experience of it.

Their power as a collective force has diminished, but their power as personal guides has increased. The gods have become more intimate, more personal, and more insatiable. They demand constant attention, shaping behaviour through psychological and social mechanisms rather than overt worship. Their power is insatiable because human desires are endless. They thrive on the perpetual pursuit of betterment, success, and fulfilment. This leads to a paradox: the more humans chase these gods, the more elusive they become. Satisfaction is fleeting, and the cycle of desire continues unabated. The gods of modernity are not static; they evolve with human aspirations.

The Lifecycle of a God

"La Vierge au Lys" (1899) and "Pieta" (1876) by William Bouguereau

Stages

- Birth: Arises where humans feel powerless. Threat or need creates demand.

- Evolution: Survives by addressing new human problems: society, ethics, governance.

- Abstraction: Persists as principle or virtue when direct worship fades.

- Internalisation: Guides behaviour psychologically, maintaining utility through culture and habit.

Some gods die at each stage, discarded when no longer needed. Some survive by continually providing value. Relevance is the true measure of power. Survival is not fate; it is service.

Adaptation and Syncretism

Some gods like Jesus and Buddha have traversed multiple stages, adapting to changing human contexts. Others, like many nature deities, faded as their original purposes were fulfilled or rendered obsolete.

Some gods get absorbed into others. The Norse god Odin shares attributes with the Anglo-Saxon Woden and the Germanic Wotan, reflecting cultural exchanges and syncretism. As societies interacted, gods merged, combining their stories and functions to remain relevant in changing contexts. This process of syncretism allowed deities to survive by adapting to new cultural landscapes.

Survival through Utility

This way a god dies. Zeus died not because he was weak, but because humans no longer were afraid of lightning. Humans aren't in search of a strong powerful god with human desires. They are in search of gods that can help them navigate their complex lives. Zeus faded away because he was selfish and petty. Humans no longer needed a god that behaved like them. They needed gods that could help them be better than they were. The gods that survive are those that help humans solve their problems, not reflect their flaws.

A god can survive multiple lifecycles by adapting to new human needs. Jesus began as a revolutionary figure challenging Roman authority, then evolved into a spiritual savior addressing personal salvation, and finally became a symbol of moral guidance in secular contexts. Each transformation allowed him to remain relevant across different eras and cultures. Jesus became a tool for various nation-states to legitimise their rule, a source of personal comfort during hardship, and a moral compass in times of social change. His survival is a testament to his adaptability and the enduring human need for meaning and guidance.

Conclusion

Gods are not eternal or inherently powerful. They are reflections of human need, their influence proportional to the problems they solve. They thrive when useful and vanish when obsolete. Survival is not divine right, it is service.

The real lesson is this: a god’s power is a measure of its utility. Those that endure teach us not absolute truths, but how humans live, organise, and project meaning. Their history is the history of human problems, desires, and imagination made divine.

Instead of asking "Are gods real?" we should ask "What needs do gods serve?" Their existence is not a matter of faith, but of function. Instead of "God made humans," consider "Humans made gods." Their power is not in their divinity, but in their utility.

God is NOT dead. Rather, God is alive and will be as long as humans have needs to be met. Till humans feel powerless and till we seek meaning in an absurd world, gods will continue to be born. Not in temples or churches, but in the hearts and minds of fellow humans trying to cling on to something greater than themselves.

God is a tool.

God is a mirror.

God is a story we tell ourselves to survive.

God is human imagination confronting necessity.

God is human utility made divine.

God is whatever we need it to be.

God is what we make of it.

God is us.